Looking at Him Looking at Them

By Jason McBride

February 08, 2009

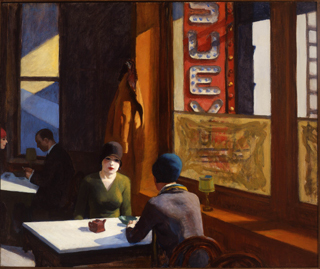

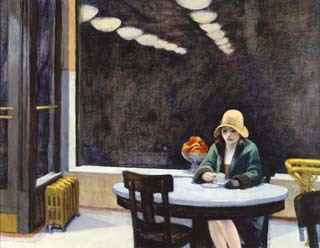

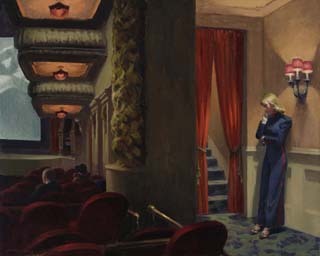

What he couldn’t have were the growing number of women frequenting public places without husbands or chaperones as the US emerged from its cocoon of Victorian values. Born in 1882, Hopper grew up in a more conservative age, then suddenly, out and about, were all these pretty, young women who seemed at once eligible and unattainable.

By scrunching down his output of thousands of pieces into 10 paintings and 3 etchings, the SAM gives us Edward Hopper, Anthropologist with Dirty Motives. Of course, all those other male painters had no sexual interest in their subjects. But the SAM makes Hopper seem creepier than the others.

They may have a point. Hopper painted in cinematic medium and long shots. His faces are robotic, almost fishlike with their pallor and beady eyes. Even the young man and woman on the porch in “Summer Evening” (1947) seem at odds with each other. There is sexual tension, but no intimacy.

What the SAM exhibitors fail to mention is the shared experience between Hopper and his subjects. They are as lonely as he, lost, stripped of the comforting constraints of nineteenth century propriety, whiling away their leisure time in cold, impersonal automats and diners.

In a way, Hopper was better off. Two years after he painted "Chop Suey," Hopper had paintings in the collections at several prominent museums, among them New York Museum of Modern Art. In 1933, the MoMA held a retrospective exhibition of Hopper’s work. Those long hours people-watching in diners yielded something other than heartburn.

Hopper was married in 1924 to Jo Nivison, a painter who modeled for the artist’s subsequent works. They lived and worked together in the same cramped Manhattan apartment until Hopper’s death in 1964. One cannot help wondering how Jo felt about standing in for the multitudes of young, seductive women her husband put on canvas.

"Jo Painting" (1936), is one of the most interesting pieces at the SAM show. We see his wife almost in close-up, with the broad side of her cheek and a burst of curls facing us as she works intently. She’s no China doll, teasing our gaze. Jo focuses on her work with a practiced banality. There is no mystery.

The SAM tag gives us Jo’s bitter appraisal of her portrait: "Sure – it’s solid – if that’s what any woman craves – solid and thick and bleary eyed and terrible creases – with luxurious curls down her back."

It seems sad that Hopper depicted his wife less sensually than the woman she stood in for when modeling. But the tragedy is that he painted her without tenderness. She looks busy and slightly annoyed. Although his standard movie-like storytelling appears absent here, it’s perhaps more subtle, hinting at a tense and frustrating marriage.